Three Writers’ Take on Tauromachy

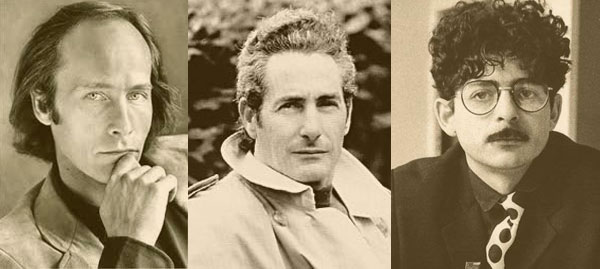

Richard Ford, Barry Gifford, Jordan Elgrably back in the day.

Best of Writers at Work | By Jordan Elgrably

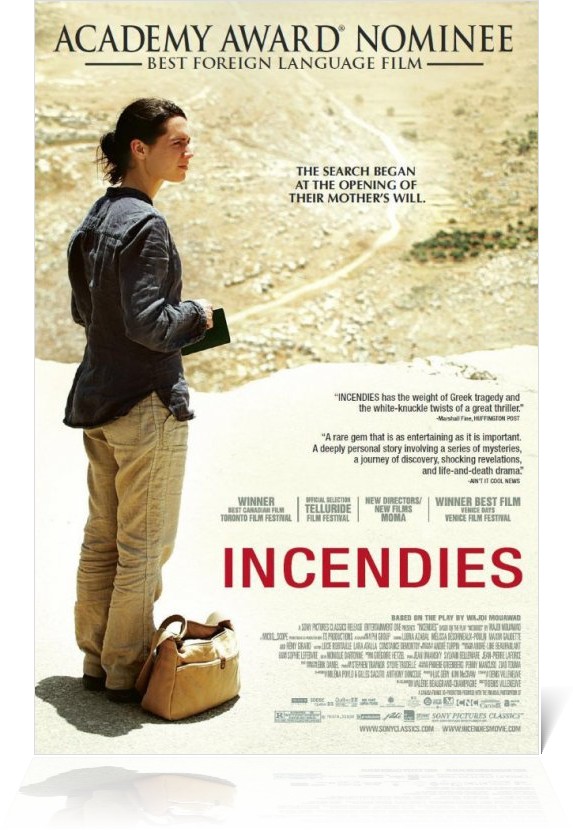

Richard Ford is the author of many novels, including The Sportswriter, Independence Day (for which he won the Pulitzer Prize) and the short story collection Women With Men. Barry Gifford’s books include Port Tropique, Back in America, Brando Rides Alone and The Phantom Father, and his credits as screenwriter include Lost Highway, Perdita Durango and City of Ghosts. Jordan Elgrably is a former expatriate journalist who was based in Paris and Madrid. His forthcoming novel is The Book of Love and Exile.

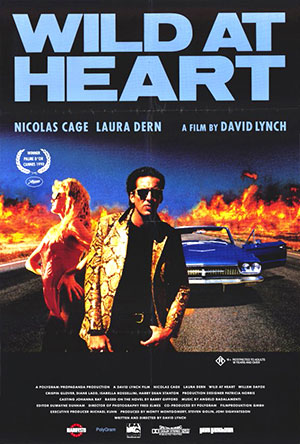

Richard Ford and Barry Gifford were in Spain on book business when they decided they’d go to the bullfights. For the authors of Wildlife and Wild at Heart, respectively—two novels with a subtext of violence—it seemed like the right thing to do. Though Richard and his wife Kristina had lived in Oaxaca, Mexico for nearly a year (the setting for Ford’s second novel, The Ultimate Good Luck), he’d never been to a corrida, while Gifford had last seen violence in the ring in Mexico at the age of eleven and claimed to remember it vividly. With true afición he talked Ford into going.

Now that the moment of truth was at hand, however, Ford had a worried look on his face—from these first row seats the gore was palpable. Gifford watched with intense concentration, his hands steepled up against his nose, as the matador raised the weapon of death and sighted along the blade. Ford glanced away. “Oh, God,” he grumbled. Did he really want to see this?

Morenito de Maracay, a dark-skinned little man, plunged the sword into the bull’s shoulders, at the base of the spine. The curved, razor-sharp estoque went in only half-way before the mulatto matador—a Venezuelan and one of the rare foreign bullfighters to make a living in Spain—withdrew it, simultaneously drawing hoots and shouts from the Sunday crowd. Morenito had gone in at the wrong angle, it seems, missing the aorta; the bull, whose name was Indolente (I kid you not), staggered like a punch-drunk fighter. A hundred feet away a heckler yelled down into the ring in a basso profundo, his face red with booze, “Anda, kill him, kill him! He won’t even notice!”

Las Ventas, Madrid

It was a taunt the diminutive Morenito could not ignore. He had just exceeded the fifteen minutes allotted him for the killing and was in a hurry to please the Presidencia. As the bullfighter flew through the air again, affecting the choreographic movement called volapié—fleet feet—Indolente lowered his horns to receive him. This time the estoque, agleam with Goyesque blood, penetrated to the hilt. All 1,100 pounds of bull thudded into the sand. But Indolente did not die on the spot. I could see his head move, shoulders slumped and eyes bulging through my zoom lens like some Picasso aberration. The second thrust had also failed to sever the great artery. Jeers and insults echoed across the arena while three trumpets—ta-ta-ta-taaaaa—sounded the trill of death. Morenito contemplated his opponent for an instant, then seized the sword by the handle with both hands and gave the two-and-a-half-foot blade a jolt in its taurine sheath. Indolente convulsed.

“The coup de grace,” said Gifford.

It certainly looked that way, yet the man to actually slay the beast is not the matador but the puntillero. Like all messengers of death, this character arrives discreetly and performs his handiwork. I saw him—a small person who looked more like a pickpocket than a corrida official—reach down with the puntilla (dagger) and repeatedly stab the bull at the base of the skull. After nearly twenty minutes of battle, then, Indolente’s soul left his bloody carcass and floated away over our heads to wherever butchered bull souls go. “Por fin!” the drunken heckler cried, his arms a semaphore in the air, “Por fin, joder!”

The roar of the crowd was a boo-hooray reaction to the bravucón (a bluff of a bull, antonym of bravo) and to a clumsy kill. Nobody tossed anything into the arena to show their disgust, nor did they wave their handkerchiefs at the Presidente. Morenito de Maracay, who that season had already slaughtered 86 bulls and slashed 38 ears—at the behest of the bullfight authorities—would not be awarded a single ear.

Ford looked into his hands with veiled emotion. In truth, he really hadn’t wanted to attend and had threatened to leave if he didn’t like it. “This,” he said, “is not my culture.” Gifford’s jaws flexed, a grim expression of acceptance; he glanced over at me to see if I was having a good time. As they dragged Indolente’s rigid remains from the Plaza de Toros, I shrugged. It was not my culture either, unless you considered that my Sephardic ancestors had lived in Granada under the Moors, long before tauromachy had taken a hold over native Spaniards and the national imagination.

It was on Saturday evening, as we were preparing to rendezvous with a few Madrileño friends at Sobrino de Botín, a restaurant on the Calle de los Cuchilleros (Street of the Knife Sharpeners), that Gifford enthusiastically invited everyone to the fights the next day. It was shortly after Easter, the season was just starting and good seats would not be hard to come by. “When in Spain...” he said. Richard and Kristina Ford, who greet virtually every suggestion with alacrity, thought it over a moment and decided yes, they’d like to go, though Kristina seemed to have second thoughts.

The authentic Sobrino de Botín in Madrid.

Calle de los Cuchilleros, one of the oldest streets in Madrid, is dense with famed if touristy flamenco restaurants, tapa bars and bodegas; to get to it you cross through the Puerta del Sol and the Plaza Mayor, then take the cobblestone steps to Cuchilleros, where you first come upon El Cuchi, the newest establishment on the street and a restaurant of undistinguished cuisine whose sole merit, brightly announced on a green and white marquee, is HEMINGWAY NEVER ATE HERE. Pointing out the marquee, I mirthfully told everyone this was where we had our reservations, at which Richard Ford laughed and said with irony, “Oh good!” A private joke, considering Ford had once told me he felt his stories had suffered facile comparison to those of Mr. Hemingway.

At Sobrino de Botín we were led to a table on the second floor; the rustic decor included an aging waiter and baroque-looking menus that read casa fundada en 1725. We ordered, each in his special brand of Spanish, but when the entremeses arrived, Kristina turned to me and confided that she really didn’t want to see a corrida. “I just don’t think I want to watch the suffering,” she said. “It‘ll give me nightmares.” In fact, I had very little compulsion to go either, but Gifford’s excitement at being in Spain for the first time in many years had infected us all. “I hit the coast off Barcelona in ‘66,” Barry had told us, “on a drug run to Morocco. Nasty experience, and I never got to Madrid.” This trip was going to be different. You could not come to Spain, he seemed to be saying, without witnessing at least one live corrida, any more than you could visit France without gorging yourself on the finest wines and cheeses.

While we were working on our appetizers I remembered a tertulia I’d once had with two young Spaniards who’d gone to bullfighting school and still loved the sport, though they’d given up any hopes of entering the ring. (A tertulia, another national pastime, is a gathering or discussion, often of a literary nature; ours had been about the bull’s suffering.) “They say that if the bull is bravo,” I told Kristina, reiterating their argument, “he’s so powerful that the picador’s pike pole and the banderillas only enrage him more. He feels little or no pain. They say that only about two out of a hundred bulls put up that kind of fight, though.”

Kristina nodded politely, she picked at her appetizer while I talked on: Wasn’t it a question of human grace and courage versus brute strength and adrenaline? Weren’t the fights more about bravery than the sadistic torture of animals? “The corrida may be a bloodletting in which thousands gleefully participate,” I said, playing devil’s advocate, “but after all, it is the art and heart of Spanish culture.”

“You know, really,” she said, cutting me off with a pleasant smile, “when I go game hunting with Richard, I try to make it a fast kill, I really do. I feel bad if I just wing the bird.”

I was trying to learn to write, commencing with the simplest things, and one of the simplest things of all and the most fundamental is violent death...Bullfighting is the only art in which the artist is in danger of death.

Or so Hemingway figured. Writers are constantly contemplating the meaning of death, as we all do, which is probably why Ford felt compelled to go, and why Gifford couldn’t stay away. Although I was not much for Spanish mysticism, I felt it explained, in part, the national culture of the corrida, the melancholy of flamenco, and the fact that entire families were able to cut each others’ throats during the Civil War, a cataclysm which appears to have been all but buried in the years following Franco’s death in 1975. The dark side of the Spanish soul, however, tends to evaporate in the Iberian sun, and it’s nowhere to be found in the alegría of Madrilenos who haunt the city’s bars until all hours of the night.

At five in the afternoon Sunday—it was exactly five in the afternoon—I walked the short distance across the sundial plaza of the Puerto del Sol and up the Calle del Carmen to the Hotel Liabeny, where the Fords and Barry Gifford were staying. I found them waiting in the lobby. Kristina smiled affably and said, no surprise to me, “You go on and try to have a good time. I’ll just stay here and read.” But Gifford seemed disappointed. “You really should come,” he said. “You’ll be missing something.” With a wild gleam in his eye, the Southern-raised Richard Ford—writer and game hunter—raised his voice from its usual soft register and said, “If Kristina doesn’t want to go, I don’t want her to go.”

Normally inseparable, there was no use arguing: Kristina would stay behind.

We boarded the Metropolitan and took the train to Ventas, the last station on the red subway line. Ford voiced his misgivings throughout the ride, but Gifford’s enthusiasm would not be muted. “It’s like mink coats,” he said. “Nobody’d be killing minks if women weren’t wearing them. I mean, all this is fixed beforehand.” The bulls-are-born-to-be-killed argument, while true, would probably not make it any easier to watch their slaughter.

It is worthwhile to consider how each author handles violence in his fiction. Barry Gifford never shrinks from it; he accepts its inevitability and reports in graphic detail, conjuring the kind of imagery which director David Lynch filmed in Wild at Heart, the film based on Gifford’s novel of the same title, and which Gifford continues to explore in his Sailor and Lula novels and their spin-offs—Night People, Perdita Durango (also a movie starring Javier Bardem and Rosie Perez). Richard Ford, on the other hand, writes of violence with quiet, almost oneiric resolve, a dreamlike quality especially evident in books like A Piece of My Heart, Rock Springs and Wildlife, where the reader is confronted with the violence latent in himself. Clearly, that novel points out, our intelligence is hardly a guarantee of humanity; something else can overtake us—nature, or wildlife—which carries us away, forcefully, from what we are or would like to be, at times when the intellect is needed most.

And yet, Ford’s reluctance to see a corrida took me by surprise. He was a famed outdoors man, after all, who enjoyed hunting and fishing as much as any of the characters in A Piece of My Heart or his Rock Springs stories; I knew that he had no particular affinity for the machismo of Hemingway, but I couldn’t see why somebody who grew up killing animals for sport in North America would object to the extravagant equivalent in Spain. I suspected it wasn’t out of any animal-loving sentimentality but a decided aversion to touristic kitsch that Ford nearly let Gifford and I go on alone.

Gifford’s desire to attend a corrida did not come as a surprise. Several years ago I discovered his first novel, Port Tropique, a fascinating story of drugs, thugs and Central American revolution in which Gifford imitates the feverishness of Conrad, the staccato rhythms of Hemingway, and mocks both legendary novelists. Enchanted by Tropique’s tough-guy character of Franz Hall, I suspected Hall might be a parody of the author himself. When we later met in Paris, my impression of the tough guy-cum-author was confirmed. While he writes poetry with the sensitivity of haiku

Startled by a bird

I clutch my heart

As if you’d flown

Out from it

Gifford has the biceps of a merchant seaman and truck driver—two of the professions he exercised before he began to make a living from his writing. And although he started out as a poet, going on to write short novels like Port Tropique, Wild At Heart, and Night People, Gifford has also written books on baseball and the horse track.

We got there a few minutes early and wandered around in front of the arena, a structure of Moorish design built in 1929 with Nasrid arches and a mudéjar ceiling at the entrance (after the Plaza de Toros in Mexico City, Ventas is the world’s second-largest arena, seating 23,000). A scalper flashed some front-row tickets at Ford while Gifford bought a tee-shirt for his teenage son. Stopping to gaze at bullfight posters on which the tourist can have his name printed as the main attraction, Ford pointed to a poster that read YOUR NAME HERE and said, “That’s the one for me.” Entering the Plaza de Toros, we did not dilly-dally on the patio de caballos or wander through the other dependencies, but walked straight into the plaza and were directed to the first row of concrete tendidos behind the wood barrera, where Ford extracted a hundred pesetas for the steward. A hundred pesetas was the price of a good seat in the era of Death in the Afternoon, circa 1932; now it might buy you a cafe con leche, a copy of the Madrid daily El País or a cheap cigar.

Bull and matador at Las Ventas, Madrid.

The corrida is six three-act sketches of five minutes per act, or tercio, in which each of the six bulls of the day are faced by two picadors, three banderilleros and a matador. In the first tercio de varas, the bull is released from the toril, or enclosure and four men on foot draw the bull’s attention with hot pink-colored capes, ducking in and out of the burladeros, those little shelters behind which all the toreros stand at the start of the fight and behind which they retreat on fleet feet when the bull singles them out for especially mean treatment. (The brightly colored capes, by the way, are more spectacle for man than bull, who is born colorblind and will never care whether you wave a red flag or a yellow swizzle stick at him.) Then the picador appears on his padded horse and is invariably attacked by the bull, who tries, usually in vain, to throw the horse while the picador jabs his pic into the hump of shoulder muscles, thereby draining the bull of much of his strength. A second picador is stationed on the opposite side of the ring should the bull turn away from his attackers. During the second tercio de banderillas, the banderilleros run at the weakened bull and plant their staves around the wounds administered by the picador. In the third tercio de muerte, the matador brings out the estoque and a cerise-colored cape and performs the final rites. After we’d watched the second of the six bulls bite the dirt, Ford stood up, knotted the waistband of his trench coat, and adjusted the beret he’d been wearing. “I told you if I didn’t like it I’d leave,” he said. “I just can’t see the sense of this.” But Gifford was enjoying the camaraderie. He flagged a refreshment vendor. “Have something to drink? You’ve lasted this long,” he said persuasively. “Why not stick it out?”

After a moment of hesitation, Ford sat back down on the uncomfortable concrete bleachers, and we wordlessly waited for the third bull to appear. When the grotesquerie began again, with the bull rushing the picador on his padded, blindered horse and the picador stabbing him with impunity, Ford frowned. “I don’t so much mind the killing and the dying,” he said. “What I don’t like is how they reduce the bull so as he can hardly resist those little bastards.” He was referring, of course, to the bandilleros and matador, who would be incapable of approaching an un-piced bull. Sitting this close, we could hear the bull bellow with pain when the banderillero jabbed his barbs into the bull’s withers. His name was name Traicionero (“traitorous one”), and he was not, our Castillan neighbors assured us as they pointed to his grey, drooping tongue, bravo.

matador and toro

Fighting bulls are raised semi-wild by men on horseback and never see a man on the ground. Once they’ve been in the arena they learn from the experience and must be killed. Indeed, the most exhilarating moment of the corrida is when the bull first emerges from the toril, spots his enemies, and charges after them. At this stage he’s still a wild animal that puts the fear of God into you, but as soon as he goes for the picador the greatest danger has passed. “Are they intelligent?” Ford wondered, speaking to a tiny, withered old Spaniard sitting near us. “Oh no,” the old man said, “but they remember. They can remember a man ten years later,” he added. “If they’re not put to death, of course.”

Boredom is one aspect of the fight you don’t count on. Compassion for the bulls, excitement, even terror—but not aburrimiento. In effect, after you’ve seen one or two bulls dispatched from the ring you begin to feel like you’re watching television; there is this overwhelming sensation that you are not actually participating in the spectacle, sitting there in the crowd engaged with your feelings, but that you’re seeing everything as if from outside. And—if you find your reaction to the bullfight is not fascination—you want to get the hell out of there. Impatience sets in, you’ve given your first yawn, you more or less forget the fight itself and watch those watching it, which is perhaps the most fun of all.

A lot of Spaniards come just to heckle. The professional hecklers are admired and prompted by the people around them. Our rubescent drunkard carried on a monologue with the bullfighters throughout the afternoon. When the bull wasn’t offering much resistance, he’d bellow, “Save your department-store discounts, we don’t want them!” And if the bull refused to leave his querencia, an area of the arena he establishes as his territory and from which the matador must draw him out for the kill, he’d cry “Que se vaya!" or “Afuera, afuera!” Meaning the matador should either hurry up and get it over with or go the hell home.

While Gifford took the corrida rather seriously, remaining silent during all the crucial moments, Ford often shook his head and poked fun at the toreros in their traje de luces, those body-hugging, sequined suits; when one banderillero scratched his genitals in full public view, Ford chortled, “I’d be doing that too if I was wearing those ridiculous pants.” Later, however, after an especially powerful-looking bull lunged at his festooned enemy and an aficionado leaned over to tell us that all toreros are gored sooner or later—superficially, seriously or fatally—Ford winced. “Listen, if one of these guys got the horn,” I asked him, “would you be unhappy?” “Yeah,” he said, “I would.” And yet, you had to wonder: if the element of human tragedy were to be eliminated, if there were no risk of a goring, would any of us have come?

A great killer must love to kill.

A certain degree of skill, grace and courage are indispensable for any man who hopes to survive in the ring, but the science, or art, of tauromachy makes a distinction between toreros who do great work with the muleta (the heart-shaped serge or flannel cape folded over a wooden stick), and the hot-blooded matadors who are more convincing in their use of the sword. It is a dichotomy of style: theartiste who dazzles you with cape and footwork is closer to a flamenco dancer than a killer; he does not enjoy the kill and often declares his distaste for it to the bullfight journalists. The proficient swordsman, on the other hand, may not have feet of velvet but he revels in the moment of truth, when he must make the kill. Spaniards with a sense of humor snidely call the latter a Mata Toros, a butcher of bulls. But whether the torero is a dancer or a killer, he knows the meaning of fear: beginning the day before the fight, he sweats profusely, his beard grows faster and he experiences the kind of stomach pains for which women take Midol.

It is the decadence of the modern bull that has made modern bullfighting possible. It is a decadent art in every way and like most decadent things it reaches its fullest flower at its rottenest point, which is the present.

You couldn’t convince Richard Ford that bulls know anything about art or decadence. In any case, the current argument in Spain against the corrida is not so much with the bred-down, semi-savage bull, the overpaid or incompetent matador, or even cruelty to animals, but that it is tercermundista—of the Third World. Bullfighting is tercermundista because it is a poor man’s sport, is bad art, is kitsch, or so the reasoning goes. Having been effectively removed from the European community by almost forty years of dictatorship under Franco, many Spaniards have come to be proud of the country’s highlighted role in the European Community; to them the bullfight is an embarrassment, an outmoded tradition which they liken to cockfights in Manila or dogfights in Mexico. Aficionados, however, claim the corrida offers some resistance to the encroaching universalization of life in the West—what some social critics have decried as the Americanization of Spain. Though commercialized and exploited for the purposes of tourism, bullfighting resists outside pressures to change, they say, unlike most other aspects of Spanish life, including popular music and the cinema. (Ever since his “Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown” was nominated for an Oscar, moviemaker Pedro Almodóvar has been accused of falling victim to the pernicious influence of Hollywood.) Conservative Spaniards insist that inculcating their children with the art and history of the corrida will give them a sense of tradition they otherwise would not have, and so you see these miniature adults, the ten-year-old girls in their frilled sevillana dresses, the boys wearing toy swords, shouting “ole!” with as much afición as their parents.

When the Socialists were swept into power in 1982, many Spaniards feared the corrida would be outlawed from existence. There was a new liberalism in the air, a desire for change, which prompted the cultural revolution, or movida in Madrid and Barcelona, and bullfighting was considered passé. Pedro Almodovar’s 1984 parody, “Matador,” showed the conflict between the corrida and the movida’s renewed values; often hilarious, the film follows a retired matador and a kinky journalist both obsessed with death and sex; in the end, with flamenco blaring in the background, they kill each other as they climax simultaneously. Aficionados needn’t have worried, though: bull-slaughter may be bad for the Spanish spirit but according to ticket sales it is more popular now than at any other time in the last 100 years. Indeed, the bull is a cash cow for the economy. In an average year nearly 25,000 bulls are killed before an estimated 30 million spectators, an industry which supports 150,000 employees and toreros, and brings in billions of dollars. Each of the five daily papers in Madrid has a Toros column, usually just after the pages of Cultura and before the sports section, and some of Spain’s best journalists are experts on tauromachy. Bullfights appear on the small screen as often as soccer or basketball. And, if you need further evidence that bullfighting hasn’t passed from fashion in Post-Movida Spain, a new nightclub recently opened in the heart of Madrid, called, honorifically, “Torero.”

The sun was a blood orange by the time the last bull was dragged from the ring. We slowly filed out of the Plaza de Toros and into the Metropolitano amidst Spaniards who joked and jostled one another in their usual noisy way; none of us had much to say, and if we did it wasn’t about what we had just seen, but about the dinner and drinks we were looking forward to. Each of us confessed to a healthy appetite.

That evening, after walking the Fords and Gifford to their hotel, I began to realize just what effect the afternoon had had on me. Far from having been instilled with afición for the corrida, I was convinced that this was to be my unique experience. Afición is a word for any sort of enthusiasm or love; in the bullring it is a passion for the fight and the element of risk to the man below; it is not a passion for the bull, who in his bluntness, in his stupidity, is a metaphor for the nothingness beyond death. At the moment of truth you see not only an animal about to be slain but the bullfighter’s fear of nothingness, which he conceals as best he can behind his mask of courage.

That very fear is what Hannah Arendt was referring to when she wrote, “Homo faber, the creator of human artifice, has always been a destroyer of nature.” The corrida can also be seen as a theatrical representation of Ende-Sein, philosopher Martin Heidegger’s term for the human condition of “existing-towards-death” or “being-for-death”; it is the brutal art of nada as expressed in paintings by Goya, glorified by Hemingway and exhausted in much of heroic world literature.

The question is, is a brutal art still art?

Quotes in bold italics from Death in the Afternoon, by Ernest Hemingway.

![Sahara [Photo: George Steinmetz]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5575e4ace4b0c73f725bc5cd/1434047166345-WCEI46KQR2AEBDFGQKTC/image-asset.jpeg)

![Palestinians living under Israeli rule have the same desire to recover their human and civil rights as others protesting against oppression across the region [GALLO/GETTY]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5575e4ace4b0c73f725bc5cd/1434136889450-PQHMP46V8PLLYFGLAFXP/image-asset.jpeg)