Denis Villeneuve's latest west-meets-east film about war and identity bridges North Americans and the Arab world.

21 April, 2011 | AlterNet | By Jordan Elgrably

Rarely has a story about modern war and civil strife so powerfully traversed generations and continents as the Canadian-Arab feature Incendies.

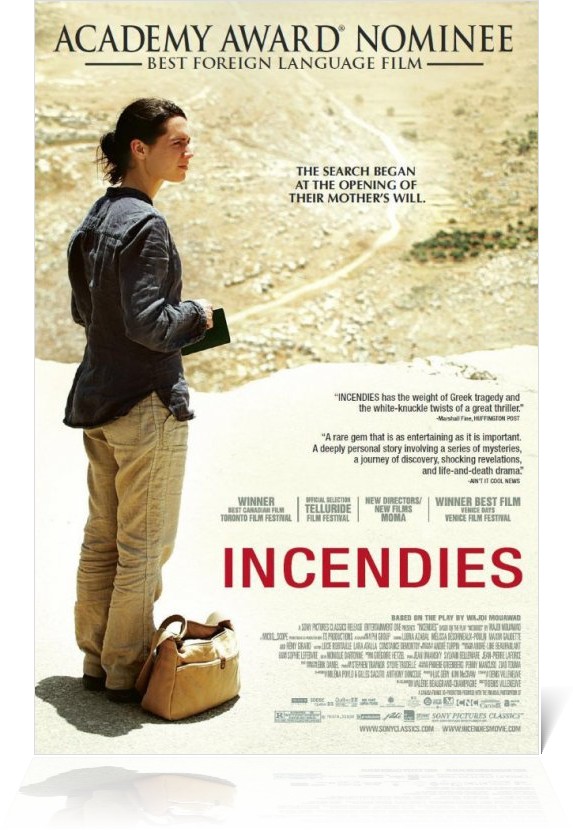

Montreal-based director Denis Villeneuve’s adaptation of Wajdi Mouawad’s three-and-a-half-hour play opens in New York and Los Angeles theaters this weekend after clinching an Oscar nomination for Best Foreign Film earlier this year. The film took home eight Genie awards in Canada, including Best Actress for Lubna Azabal. Incendies features a little-known Canadian and Arab cast, yet tells a gut-wrenching tale that takes no prisoners.

“Incendies” refers to the fires of war that can consume a country, a family, and indeed an entire generation. While Mouawad emigrated to Canada as a child from war-torn Lebanon (where civil strife stretched from 1975-1990), he set his play in an unnamed Arab country. The film was shot in north Jordan and used many amateurs, including Iraqi refugees, yet for those familiar with Lebanon’s internecine conflicts between Muslims, Christians and Palestinian refugees—as well as Israeli invaders and Syrian interventionists—the scenes in Incendies strike close to home.

One of only two international Arab actresses familiar to western audiences (the other being Palestinian-French star Hiam Abbass), Belgian-Moroccan Lubna Azabal plays the central character of Nawal, a freedom-fighting and ultimately long-suffering woman who becomes a lover, a prisoner, a mother and an émigré.

Previously, Azabal left a powerful impression in Hany Abu-Assad’s Paradise Now, in which she starred as a peace-loving, contrarian sister to a would-be suicide bomber. In the Israeli indie pic Strangers, she shone as Rana, a Paris-based Palestinian mother who unexpectedly falls in love with an Israeli during a visit to Berlin. Azabal has also co-starred, albeit less memorably, in Bodies of Lies and Exiles.

In Incendies, Azabal gives remarkable performances as both a young and middle-aged woman. An early axiom in the film is jarring and provides just the right note of foreshadowing: “Childhood is like a knife stuck at your throat.”

When notary Lebel (Rémy Girard) sits down with Jeanne and Simon Marwan (Mélissa Désormeaux Poulin, Maxim Gaudette) to read them their mother Nawal’s will, the twins are stunned to receive a pair of envelopes—one for the father they thought was dead and another for a brother they didn’t know existed.

In this enigmatic inheritance, Jeanne sees the key to Nawal’s retreat into unexplained silence during the final weeks of her life. The college-age daughter, who does not speak more than a few elementary words of Arabic, decides she must travel to the Middle East to dig into a family history of which she knows virtually nothing.

Incendies is as much about finding one’s past as it is about a country wracked by civil war. An Oedipal tale with surprising twists, we see Jeanne and Simon Marwan, the daughter and the son, retrace the same route traversed by their mother decades before.

Early in the film, devastated by the death of her Palestinian lover, Nawal flees her town and family for the big city, where she begins a new life as a college student. She contributes to the city’s muckracking newspaper, published by her roommate’s father, who insists that, “ideas will survive only if we are here to defend them." When things heat up in the streets between Muslims and Christians, citizens and foreigners, she finds herself, willy-nilly, an activist for her country’s sovereignty. Ominously, Israeli fighter jets fly over as hell breaks loose.

In Incendies one observes the residue of colonialism and how it bleeds into sectarian strife, Christians against Muslims, citizens against refugees. The structure at times reminds one of films like Memento or The Usual Suspects, particularly in scenes where the mother transitions to the daughter decades later and vice versa, often seamlessly, as if the daughter and the mother are the same person.

Denis Villeneuve, a soft-spoken filmmaker in his early ‘40s, explained during an interview that the film is a metaphor for the fact that children have to rid themselves of their parents’ anger. The character of Simon Marwan—the angry young man who has no desire to dig into his mother’s Arab past—could be the director’s alter ego. Said Villeneuve, “What is a Canadian who knows about snow doing making a film about war?”

But Villeneuve was transfixed when he first saw playwright Wajdi Mouawad’s 3.5-hour long Incendies in 2004. After several years and many rewrites of his adaptation, he says Mouawad saw the film four times and embraced it. Nawal’s long-suffering character was based on a historical figure, a woman named Souad Beshara, who attempted to murder a major Christian militia leader and spent 10 years in a southern Lebanon prison.

Incendies is an Arab story yet only one of myriad possible stories that Americans can discover about the Levant where it takes place. The film was shot in just 25 days on a modest budget yet it has the feel of a vast and sweeping epic. The storytelling is dense, the characters brooding and unforgettable. Villenueve has made a deeply personal and poetic film that stands as a testament to the will to survive and protect one’s family from the horrors of war.