The Dream Factory: Oliver Stone and Barry Gifford Converse on the Production of Art in a Mass Market Culture

1995 | Matador [Madrid] | Interview By Jordan Elgrably

IN A WORLD THAT IS NOW ONE HYPERTROPHIED MARKETPLACE, the products of art—high or low—increasingly owe their success or failure to the mechanics of good distribution and promotion. In this mass market context, "global economics" is another phrase for corporate politics, hence a New World Order that spawns treaties such as NAFTA and GATT, hence we have dominant cultures exporting their product regardless of quality. To quote Hollywood's earnest knight, president of the Motion Picture Association of America Jack Valenti, U.S. films "are America's most wanted export and the envy of all other nations." His statement, one notices, says nothing about quality, but implies that if the product sells, it must be good.

Vast corporations, usually of the multinational variety, are in control of the marketplace, not just in defense, energy, transportation and computers, for instance, but in the production of films, music, books and other cultural wares. Frequently a corporation that has a controlling interest in one of the aforementioned industries also owns television stations and newspapers. So what happens is that these monoliths of industry, business and media, which exist in concert across borders and continents, are often exempt or nearly exempt from most government regulation. International capitalism, the "free market," has not only endangered democracy and removed the teeth from socialism, but it has begun to play havoc with our cultural sovereignty, with what makes each culture unique.

Few would argue with essayist Pico Iyer when he insists that, "More and more of the globe looks like America, but an America that is itself looking more and more like the rest of the world." In its pursuit of the middle-class dream of acquisition, comfort and convenience, much of the western world is indeed coming to resemble the U.S.A.; and yes, the United States, having welcomed millions of immigrants, is a vague reflection of world cultures which appears to function in a democratic fashion. But appearances, as the Emperor's subjects will tell you, are deceiving. The fact is that the American media and the market economy have been instrumental in the selling of mass market culture around the world, and the principal beneficiaries of this trend have been the economic elites, not local communities. CNN now reaches nearly 150 countries. U.S. chains such as MacDonald's, Pizza Hut and 7-Eleven are found in the most remote regions of the planet, and MTV––a channel which is almost pure entertainment product, with less than 15% airtime devoted to real news, information and non-commercial programming––is watched in some 75 countries by more than 50 million young people.

The discriminating consumer of mass market product undoubtedly suffers from chronic cultural indigestion, what with all the available product out there. Yet if you consider yourself cultivated you probably refuse to even think of yourself of as a "consumer" at all––while you're constantly bombarded by the best and worst of popular culture, the more intrepid among you always seems to be seeking out the singular artist, the one-of-a-kind vision which confirms your own non-conformist dreams and desires.

Oliver Stone with Barry Gifford.

OLIVER STONE AND BARRY GIFFORD MAY BE TWO SUCH ARTISTS, because while their films and books do not always appeal to mainstream tastes, they do seem to have struck a chord in a wide range of moviegoers and readers. As a writer, director and producer Stone has learned how to skillfully manipulate the system to get his films made and distributed; he's become expert at getting the media to talk about his movies and getting the public to go see them. This takes nothing away from their artistic merit, it merely demonstrates that today's savvy artist bears little resemblance to yesterday's auteur, who had yet to master the marketplace.

“I think a lot of movie themes have had an anti-corporate, anti-big business flavor. The problem is that the enemy is hidden. The subtlety of international megacorporations who control your lives is so persuasive and seductive and it’s such a truth that it’s almost like attacking your mother or your father. And that’s a cultural no-no. You cannot bite the hand that feeds you.”

Apart from having mastered the film business, as opposed to film art, Stone has taken to heart Flaubert's insistence that the artist is the disease of society. Ever willing to spit in the face of authority, to defy convention and reject idées reçues, Stone's strength is that he knows the weight of words and the shock value of images; a wizard of the art of filmic manipulation, he consistently challenges official mythology for the sake of hard-hitting, fast-paced drama. He is a cineaste who talks frankly about "the relativity of truth," and he understands what Rolling Stone columnist Jon Katz pointed out when he wrote that today, "young viewers and readers find conventional [media] of no particular use in their daily lives––because they've been educated by MTV and rap music and raised on traditions of outspokenness and hyperbole."

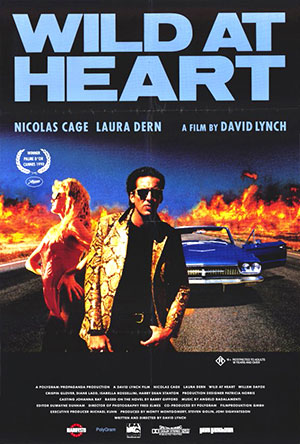

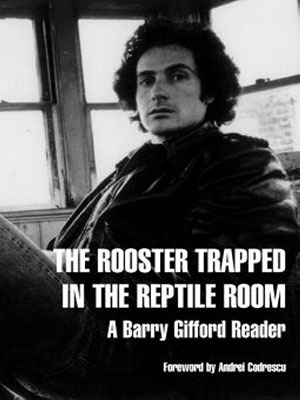

Stone uses hyperbole and exaggeration to dazzling effect, and in this he and Barry Gifford have something in common. Gifford, who labored quietly behind the scenes for years as a poet, then novelist, first gained notoriety in 1990, when David Lynch made a movie from his novel Wild at Heart and won a Palme d'Or at Cannes. Since then, Gifford has published a series of novels that grew out of Wild at Heart (among them Sailor's Holiday, Night People and Arise and Walk) which have been translated into several languages and garnered him something of a cult following, especially in Europe where his books tend to outsell their American editions.

During his years of relative anonymity, Barry Gifford also labored as editor of the Black Lizard imprint of noir fiction, a series that included such pulp giants as David Goodis and Jim Thompson, among others. In rescuing authors who were in some cases long dead and out-of-print, Gifford learned a thing or two about the vagaries of the publishing world, and while the experience may have had little effect on how and what he writes, it undoubtedly provided an education in mass market economics.

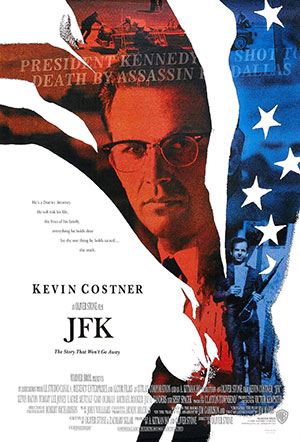

Despite the fact that their work isn't usually easy to digest, Oliver Stone and Barry Gifford enjoy a healthy share of their respective youth markets. They also attract older, more sophisticated consumers and have in the bargain received a great deal of criticism from traditional or conservative corners, Stone for challenging the official history of President Kennedy's assasination in JFK, and for attacking the objectivity as well as the scruples of the media in Natural Born Killers; and Gifford for using ultra-violent imagery in his novels to provide a satirical look at the American South.

And, when we take a closer look, we find that the two have even more in common: Born in New York City in September 1946, to a Jewish father and French Catholic mother, Oliver Stone early on proved himself a staunch individualist. Drunk on literature, he dropped out of his first year at Yale and went abroad. He tried to write a first novel at 19 while living in Mexico, then joined the merchant marines. Upon his return to New York––bored with the possibilities of civilian life––Stone joined the U.S. Army and went to Vietnam, an experience he recorded in Platoon. After his stint in the war, he studied film at New York University Film School and thereafter began his slow ascent to the summit of the American film industry, along the way winning three Academy Awards and numerous Oscar nominations. Stone is currently developing several new films for Ixtlan, the production company he founded in 1989 shortly before making The Doors.

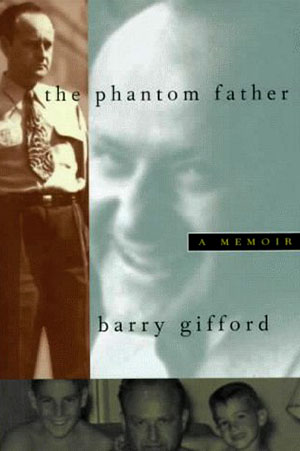

Born in Chicago in October 1946, to a Jewish father and Irish Catholic mother, Barry Gifford grew up on a steady diet of film noir and pulp fiction. Fresh out of high school, he won a baseball scholarship to the University of Missouri, but inspired by the stories of Jack London and Jack Kerouac, the 18-year-old Gifford dropped out of college after that first year and went to London, where he began to write poetry, compose rock music and play guitar in a band. He then signed up with the merchant marines and toured the world, including a stint in the Far East. Eventually settling in the San Francisco Bay Area, Gifford labored as a music journalist and a truck driver to support his young family. More recently, his novel Night People won Italy's prestigious Premio Brancati, and Harcourt Brace is publishing his new novel, Baby Catface in the fall. Gifford has written a screenplay based on Jack Kerouac's novel On the Road, for Francis Coppola; adapted his own novel Perdita Durango to the screen for Bigas Luna; and penned a libretto, "Madrugada," for composer Toru Takemitsu, which will be put on at the Opera de Lyon in 1997.

GIFFORD FLEW DOWN FROM HIS HOME IN BERKELEY to converse with Stone in Los Angeles. The meeting took place in the office of Stone's production company, Ixtlan, which occupies the sixth floor of a building that overlooks the Pacific Ocean in Santa Monica. The week of their encounter, much of California was struck by a freak storm front that blanketed the state with torrential rain. Flash floods left thousands homeless and caused several deaths, prompting President Clinton to declare California a disaster area. In Los Angeles' nearby San Bernardino mountains, local residents were calling this "the 500-year storm," so drastically was the topography scarred by nature.

As it happened, Gifford arrived on the last flight into Burbank Airport before the control tower shut down that morning's flights. "I feel like Hugh Conway in Lost Horizon,' he said, referring to the Frank Capra film in which actor Ronald Coleman plays a British adventurer flying down through clouds and fog to land in the mystic land of Shangrila. Indeed, the ordeal of actually getting to Stone's office in one piece was further complicated by a long, plodding drive through flooded streets and lashing rain that reduced one's depth of field.

Azita Zendel, Stone's trusted assistant, lead us into the director's office and returned with steaming cappuccino and mineral water for all. After a few casual introductions—Stone and Gifford had never met until today—the afternoon began with a discussion of their respective fathers and family history. Although we had come armed with the warning that Stone likes to take people out of their comfort zone, the conversation remained calm and cordial throughout.

BARRY GIFFORD My father was a Chicago racketeer. He came from a family of non-religious Jews who emigrated from Bucovina (which was then part of the Austrian Empire and is now in northern Romania) to Vienna at the turn of the century, and from there to the United States. They weren't accepted or liked by other Jews, in fact they were described as shtarken, Yiddish for strong or tough. My dad was always mixed up with Irish and Italian gangsters. He took on different names, more for the purposes of dodging the law and being involved in nefarious activities rather than trying to hide the fact that he was a Jew. My father wasn't religious, he never went to synagogue, he died when I was 12 years old. My mother's family emigrated from Ireland to England and Anglicized their name from Cohan to Colby because of the obvious prejudice against the Irish. Of my father's various names, the one my mother preferred was Gifford. My full name is Barry Colby Gifford. Barry means "spear carrier" in Celtic.

OLIVER STONE I've never gotten to the bottom of my father's history. I think he was probably of Northern German or Latvian origin [the name was originally Stein]. My father was never religious, he was always strongly atheist—almost but not quite. He didn't like the rituals, the traditions, the superstitions. My mother was a Catholic in rebellion against her Catholicism, my father was in rebellion against Judaism, so what did I become? I became a Protestant a result of all this. They sent me to Sunday school and I basically downloaded on a very American kind of compromise.

GIFFORD Your father must have experienced anti-Semitism and wanted to get away from that.</p>

“[D]issent comes at a heavy price in this culture. For a culture that celebrates the rebel, I find that most of it is lip service. Conformity rules; it reigns pretty much everywhere in the world. I think it’s always hard to cut out on your own and do something different from the tribe.”

STONE Yes, that's partly what fueled him, because he would say to me, "Don't stand out—don't bring attention to yourself...He warned me about a lot of things that happened in my life. Unfortunately, like most sons, I didn't learn my lessons from my father, I had to learn them for myself, from my own mistakes.<

ELGRABLY And yet you've built a career out of standing out in the crowd.

STONE Yes, but dissent comes at a heavy price in this culture. For a culture that celebrates the rebel, I find that most of it is lip service. Conformity rules; it reigns pretty much everywhere in the world. I think it's always hard to cut out on your own and do something different from the tribe.

ELGRABLY Isn't there some irony in the fact that while you started out as the out-spoken new kid in town, the rebel, the anti-Establishment filmmaker, you're now a giant in the Hollywood system?

STONE If what you say is true, it's a position that's been carved out of acid and rock, believe me. A giant is somebody who, generally speaking in this business, is a box-office giant. Although some of my films have done well, I can hardly be called one of the top five or ten giants, no. I've done well in spite of the subject matter, I feel. I'm always on the edge, because with each film I have to re-earn my way. Each time out I'm trying to make a new movie and each time I have to struggle to get the financing, if it seems that the subject matter is difficult or controversial. They don't say to me "go and make the movie because you're controversial," no.

ELGRABLY Both of you have provoked the media over your use of violent imagery; the question is, what can fiction or film say about violence that reality isn't already saying?

GIFFORD It can be an echo or portrayal of reality, although what I try to do is go a step further in showing the absurdity of reality, which is another way of talking about satire. There are critics and readers who seize upon the violence as sensationalism, but they either don't get it or they choose not to see the other side. They also don't like the class of people I'm writing about, usually white trash and poor blacks and Latinos in the South. The [elitist] New Yorker audience doesn't want to read about that. Yes, there's a lot of random violence, but there often is random violence out there. I've seen it, you've seen it, but this doesn't mean I'm not appalled by it, and I'm not inured to it, either. Do the people I write about not have much of a voice in literature? They don't have any voice in literature. Yes, there are novels by blacks and Latinos and whites who grew up disenfranchised and underprivileged; I'm not pretending to speak for them. But readers aren't accustomed to reading about this class of people, not in this context, not where they're shown in a humane fashion.

STONE You asked what fiction can do that reality can't. Natural Born Killers (NBK) is very much about the '80s and '90s, to me, about the sense of mass hysteria and hypnosis of the media. When we started, it was going to be a surreal piece. Then you had the Menendez brothers, the Bobbitt case, Tonya Harding and O.J. Simpson, so now it's become a satire. When I was a kid, the Bobbitt case would have been in the National Enquirer [a high-circulation tabloid]. A woman cutting off a man's penis is a sordid, jokey story, but it became a national hit, like a mini-series, in the sense that it became a money-maker for the networks...What a movie can do, or what a piece of fiction can do, is posit that madness, describe it and codify it so that we're able to look back and think about it. I was accused of exaggerating in NBK, in exaggeration resides satire, and in satire are the shards of truth. Natural Born Killers, Wild at Heart, Blue Velvet, these are all stories that are saying look at this insanity, look at this absurdity.

GIFFORD I think one of the greatest pieces of satire I ever saw was when Mel Brooks had Moses coming down the Sinai [in History of the World, Part I], and he was carrying three tablets, and Moses starts speaking and he says, "I brought you these Fifteen Command—" and he drops one of the tablets and it shatters into dust. He looks at it and he says, "—I brought you these Ten Commandments." Whether the satire is coming from Jonathan Swift, who suggested that the poor eat their children in order to survive, or Mel Brooks making fun of Moses, there's truth in it. Whenever an artist shows a little audacity, he's not going to be universally loved. David Lynch knows he's not going to be universally loved, but he has his vision and you have to respect it. The same is true for your films. And, as you say, sometimes there is some prescience involved. When I wrote Night People I had this lesbian couple of serial killers, Big Betty and Cutie Early, and then when the book came out a year later, Aileen Wuornos was in the news as the first female serial killer. Critics and interviewers wondered if I had based my characters on the Wuornos case, but when I was writing I was not aware there were any female serial killers.

ELGRABLY Like Oliver, you also face down accusations of relying on exaggeration and sensationalism to make your point.

GIFFORD There's a scene in Arise and Walk in which an ex-convict named Spit Spackle remembers an incident from his childhood, when he comes into his home and finds his mother nursing the baby, and the baby's fallen asleep in this poverty-stricken tenement. And a rat has come along and gnawed off the nipple of the sleeping mother. A reader said to me, "How could you write such a horrible thing? That sounds too sensationalist to me." Yet this story was told to me by a painter who'd heard the story from his grandmother. It happened to her in New York many years ago. I've been accused of making things up to horrify people on purpose. What can I say?

STONE I think you were perfectly valid in restating that story. It happened, and even if it did not happen, I think it's defensible.

GIFFORD When I write about these terrible events and flawed characters, their histories are very carefully explained, in terms of their genetic and environmental background. What pissed people off in Night People, for instance, is that I show the sweetness and tenderness of these women toward one another and yet they're out there committing murder. They're obviously quite mad, but they do have an internal life. For whatever reason, these women feel so locked out of the norm, of the perceived reality, that they have to recreate their own family life. It's really Us against Them. You see it in people walking around in the street all the time: it's me against the world. And so it's not difficult to see why such characters react with extreme violence, because they've been mistreated, or misled, or just born into their circumstances, born bad––however you choose to view it scientifically. If you don't believe somebody's born bad because of their genetic heritage, and you're not a believer in social biology, then you put everything down to environmental situations.

STONE The kids in NBK are white trash who find their only sense of empowerment in killing. Their mothers and fathers are really pieces of work. Exaggerated or not, it's more or less true for a lot of kids in this country who come up in a very negative environment, where the inner cities are fucked and a lot of ethnic tribes are growing up in a hostile, negative environment that is only going to create psychopathic behavior...Once you've killed your mother or your father, in whatever spiritual dimension you exist, you know you're on the road to hell. Even if you have all the justification in the world to kill your parents, you're doomed in some spiritual way.

ELGRABLY One gathers that the film medium, for you, serves not only to demonstrate but to titillate, even provoke your audiences?

STONE I think it seeks to elevate the consciousness, sometimes through shock, but not always. Sometimes through irony and humor and wit.

ELGRABLY Is it conceivable that an artist could go "too far"?

STONE No. I think that "too far" is an aesthetic choice. Too far in the sense that he hits too many bass notes, or emotionally disturbs the audience, these are an aesthetic choices. "Too far" is a matter of your own conscience, too. But you never know. Jackson Pollack in his day certainly turned off the mainstream. Many people at that time referred to his work as "vomit." And now his paintings have another aesthetic meaning. In fact I'm very wary about the usefulness of criticism and judgment.

ELGRABLY The photographer Sally Mann has been viciously attacked by conservative critics for her portraits of her nude children, which they described as child pornography, while she intended them as documentary art.

STONE This is an age-old problem. Is [Hieronymus] Bosch a creature of the devil, or is he painting a metaphor of the world?

ELGRABLY It is amazing that in spite of all the incredibly violent images and weird stories we've seen in recent years, people continue to be shocked and dismayed at all.

STONE Natural Born Killers is a good case in point. It goes to show that at least shock is available. That means we have passed a barrier or boundary of some kind...

GIFFORD People are always attracted by the weird and the violent, and sometimes they want to know that there's a flaw in the design. It's not enough that Michael Jackson makes music that millions of people love to listen to; the fact that he may be a pervert is much more interesting to them.

ELGRABLY Western society seems to be convulsing with a permanent confusion over values. As artists are you aware of the internal value system in your own work? Oliver, you've begun to explore Buddhism, for instance, in your life and your films.

STONE I think that spiritualism in movies is a luxury—most people have a life of struggle and conflict and they go to movies for reasons other than to look for an alternative cultural system..."In Heaven and Earth" we tried to posit the idea that a woman could go through life and forgive her enemies, find forgiveness in herself and reach a higher level of enlightenment through Buddhism. The picture was unsuccessful. The underlying message of the movie was extremely resented. It was distorted by the media into my somehow being anti-American, because I preferred the Vietnamese character and the American husband commits suicide...

We are a very secular, information and result-oriented society. There's very little faith in the right side of the brain type of thinking, or mysticism or what they call spirituality...Films, I feel, should be like the great Hindu and Buddhist ideographs I saw on the temple walls of Southeast Asia. Massive paintings and murals telling common tales, you know, tales of danger, fear, death, heroes, elephants, love, the birth of children and new kings, new dreams. Kings always have dreams in these ideographs. It's an interesting dream life. They worship dreams. Holiness in ritual, in art, in entertainment. I tried in my own way, with Platoon, Doors, Born on the 4th of July and JFK to tap into this national American conscience of the '50s, '60s and '70s...

I sometimes think that America—unlike the Sioux or the Buddhist societies I've seen—is really torn apart by opinion makers, and by too much doubt. A theocracy of doubt and skepticism divide us in a quarrelsome Athenian society where individual artistic achievements are suspect as attempts to enrich ourselves, or as political propaganda. If film is going to exist as spiritual revival for the country or the tribe, then it must include dissent and controversy, because film must challenge the thinking and fashion of the time. Film should try to peel back the lies.

GIFFORD I think what I'm doing is what I've always been doing—listening and observing and writing down what I hear and see. Decades before I ever published anything, when I used to write stories and poems, a high school friend—this guy's a carpet salesman in San Diego now—said to me, "I've always thought of you as a historian." And another friend who lives in Philadelphia, many years later, said, "you're just writing history." There must be some truth in it.

Starting in 1988, I began writing out the Southern side of my life. I never had before. I believe that you really are pretty much formed by the time you're 12 or 13 years old. Now a lot of what I write about in these books is the fundamentalism of the Deep South. [Gifford spent much of his early life living and traveling through the southern states of Florida, Louisiana, Mississippi and Missouri.] As a child I was fascinated by the theatricality, the arrogance of the Catholic Church. They said this is it, we've got it here, you've got to get [salvation] here. Then you had the Bible-thumping Baptists. I'm horrified by this use of religion. I think everything disastrous that's happened in the history of the world has been in the name of one God or another. You think the Catholic church is benevolent? The hell with the Catholic church—they're business people. When they close down churches in poor parishes all over the United States, because they're not bringing in enough money, because the white people have moved out of the neighborhood, and yet there are people there who've been going to the same church for 30, 40 years—they don't give a damn about those people. It's happening in San Francisco, Detroit, Chicago, all over the country.

Churches are businesses. They do what they do as long as it's in their interest. Fellini made his films about it. That's nothing new. More recently there's been this reversion to fundamentalism. People are getting more and more desperate. I'm not, by the way, denying the existence of God. I'm just talking about any institutionalized religion—any institutions, period. I was never into joining. I'm not a joiner, I'm not part of any group. There's no generation around me—and that's another difficult thing in terms of marketing. Where would Jack Kerouac be without Allen Ginsberg and his continual promotion of the Beat Generation over the last forty years? I mean, there's strength in numbers, in the group. Back when Lawrence Lee and I were doing the research for "Jack's Book" [a biography of Kerouac], there were writers we interviewed who did not want to be associated with the Beat Generation. They didn't want to be associated with the word "Beat", they wanted to be taken on their own terms. But now, for some of them, it's become their only claim to fame. They cling to it with the scraping of their fingernails, they do everything but tattoo the word "Beat" on their foreheads.

[Stone leaves the room for a few minutes to take a phone call from actor Arnold Schwarzenegger regarding "The Planet of the Apes," a picture Stone is producing. He later smiles at the mention of Schwarzenegger's name and says, "That was Arnold calling."]

“I remember being scared to death the first time I walked into a bookstore and I realized that I was staring at the same book, stacked in a huge pile from the top down to the floor. In the past, where you might have had a hundred different titles on the wire rack, now you find ten or fifteen, so you don’t have as much choice. Lack of choice and availability changes the stakes for a writer.”

ELGRABLY If at present nearly everything boils down to distribution and marketing, how does this affect the filmmaker or the writer's story, and the quality of the work?

STONE I think it's really hurt it. I think packaging is a 20th-century phenomenon. Because television has reached new megalevels of competition, a negativity has set in where you don't necessarily have to be good, but you do have to destroy your opponent. You destroy the idea of your opponent. There's more negativism in the press that I've ever seen in my lifetime. Also, since I graduated NYU in 1971, film costs have gone up enormously, and the marketing costs of films have gone up even more. Now they're spending huge amounts to market each film and it's killing the budgets, the profitability of movies, making the risks harder to take. I've heard the same thing on a lesser degree with books. I know that publishers complain that they're being eaten up by [volume] book chains, by conglomerates that are buying them because they can't get their books out into the bookstores. And because so many bookstores are owned by these huge chains, the smaller houses can't get the shelf space.

GIFFORD I remember being scared to death for the first time when I walked into a bookstore and I realized that I was staring at the same book, stacked in a huge pile from the top down to the floor. In the past, where you might have had a hundred different titles on the wire rack, now you find ten or fifteen, so you don't have as much choice. Lack of choice and availability changes the stakes for a writer. Same thing with the movies—you go to a multiplex, seven out of ten screens are taken by Arnold [Schwarzenegger and other Hollywood studio fare]. I remember David Lynch telling me that when he wanted to re-release Eraserhead in this country, the so-called art theatre circuit was reduced to 45 screens in 17 cities [this in a nation with nearly 25,000 screens]. When I first moved to Berkeley, I remember being shocked because you could go to fifteen different theatres to see independent films, foreign films, art films. Now there's only one venue, and that's just barely surviving.

STONE Marketing has responded to an attention span that's been, let's say, diminished because of the tremendous availability of new product. At the same time, television seems to have cut into attention spans, and so has computerization and cybernetics—they've speeded up the process of selection and somehow they've enhanced the negativity and lack of reception toward things that don't immediately fit into pigeon holes. It must be harder for you, Barry, because the stuff you write is off-beat.<

ELGRABLY Pico Iyer commented on this recently when he wrote, "I worry about the relentless acceleration of the world, the dramatic shortening of our attention spans, and the temptation, under a bombardment of images, to value information before knowledge, and knowledge before wisdom." But isn't it the media's business to condense, simplify and sell information as entertainment, rather than convey knowledge or wisdom?

GIFFORD When "Wild at Heart" came out, critics commented that the film was totally unrealistic, they described the violence as cartoonish, but they didn't catch the satire in it. What they wanted to promote was the controversy between me and Lynch. They asked me if I resented what David had done to my novel, and I said no: he made his movie, I have my book. And they hated that. In the novel most of the violence takes place off-stage, while in the movie David put a lot of it on-stage. He took all the backstory and enacted it. The criticism at the time was that he had sensationalized the material. Was it gratuitous? It wasn't for him. He was the filmmaker. I said then that if I were going to make the film, I would have had Nicholas Ray direct it and it would've been made in 1958, with Paul Newman and Joanne Woodward. But the media wanted to write about conflicts between David and I, not the fact that I had a great time [laughs]. I saw his Wild at Heart as a big, dark musical comedy.

STONE When the media does not like a film, there are no ends to which they would not go to discredit the film. They're very good at dishing it out, but they rarely report the actual content of what you say. I've been quoted a lot, as you know, but 80% of the time it's a misquote or out of context. After "JFK" people asked me if I had had any trouble from the C.I.A., but the greatest pressure came from the media. They attacked that movie before it was even made; a copy of the screenplay was stolen from these offices and disseminated to journalists [who were vehemently opposed to any conspiracy theory of President Kennedy's assassination]. The fact is that we have very little relationship to government in our daily life. Our real relationship is to media, because we get most of perceived reality, or received information, from media. I've always tried to affix the problem not so much with government but with the media. The greatest concentration of power is in the media, far more than in the judiciary, the executive branch or the legislature. And I'm not the first to say this—Nixon actually said it when he was run out of office in 1973.

[Stone is developing a feature about Richard Nixon; in his book The Powers That Be, historian David Halberstam, talking about the corporate media, made the claim that he Los Angeles Times in fact "created" Nixon by making him a political player.]

These [media] corporations, in my opinion, distort the reality of the world around us.

ELGRABLY Noam Chomsky would argue that the media manufactures our consensual agreement of reality, but he wouldn't entirely let government off the hook.

GIFFORD People are hard-put to believe the government line about anything anymore. I think they want to believe in a conspiracy theory, because it's more intriguing, it's Us against Them again.

ELGRABLY The late muckraker I.F. Stone always insisted that, "Every government is run by liars and nothing they say should be believed."

GIFFORD You know, I grew up in a sort of cynical way, because as a kid I was around racketeers and I would hear about how so-and-so is on somebody's payroll, political figures, sports figures, and how everything was down to the fix. My dad ran a book out of the basement of his place, but he never bet on a horse in his life. He said, "I'll never bet on anything that can't talk." This is a very cynical way for a kid to approach life, thinking about everything in terms of the fix, whether it's a political assassination or a horse race.

ELGRABLY Why don't we see more films like "Citizen Kane" today, films which take on the great government and corporate myths?

STONE I think a lot of movie themes have had an anti-corporate, anti-big business flavor. The problem is that the enemy is hidden. The subtlety of international megacorporations who control your lives is so persuasive and seductive and it's such a truth that it's almost like attacking your mother or your father. And that's a cultural no-no. You cannot bite the hand that feeds you, the hand that gives you money, gives you a job, security and food and provides you with a defense establishment, and basically provides you with cradle-to-grave security. That's the idea being promoted by beneficial capitalism, which is not small-business capitalism but big-business capitalism. Corporations have their hands in our pockets so deeply that they hardly pay taxes anymore. In this country [real] corporate taxes have dropped from about 25% to 7%.

Most of the money moves around the world now. It's not American money. There's a positive side to that, in that we don't have nationalism anymore, although we have a stupid brand of nationism, and fundamentalism, which Barry writes about. I'm telling you something very contradictory here. My feelings are that supra-nationalism is McDonald's, yet McDonald's is not American, McDonald's is everywhere. The money just moves from bank to bank. It's just a wire transfer. That's why we don't readily attack it, because it's part of our system, it's in you. You're bitten by the virus; how can you attack what you are?

GIFFORD Frank Capra made several films that were, on the surface at any rate, critical of big business, but I think that while he was expressing a dislike of greed, of manipulation, what he was really doing was reinforcing the American system. I'm not sure there is anything wrong with free enterprise itself, it's greed that's a problem. There's always somebody who wants to take 15 cookies and leave you one.

ELGRABLY Isn't "New World Order" merely a euphemism for "corporate dictatorship"?

STONE [long pause]...Ah, I would prefer the phrase "corporate control," or "corporate supra-nationalism." Competition is still a factor.

ELGRABLY How can cinema represent struggles for social justice and economic equality?

STONE Through imagination. Films can deal in...class warfare and struggle, but it would have to be done with a leap of the imagination to engage an audience. The adage is always true that people will not go to the movies to be educated.

ELGRABLY The second part of the quote from Pico Iyer goes on to say, "I worry about the intrusions of the media in all our lives, whether as subject or object...[and] about the increasing loneliness in America, where family and community are sometimes replaced by technology."

GIFFORD He has a right to be worried. Nothing's going to stop this technology from advancing, except the end of the world, which is advancing faster than the technology. The environmental situation is so dire that it's a race.

ELGRABLY [to Stone] Do you ever worry that film might be in danger of becoming too much about the technology it uses?

STONE Absolutely. I think that filmmakers have a lot of weaponry [at their disposal], and they sometimes don't concentrate enough on life experience. They have ignored that because the money is in shock and sensationalism. You can always make the imagery, but the hardest thing to do is to create an internal dialogue, an internal tension. That's the key to good screenwriting. I think screenwriting is a wonderful art form that has been neglected. There is a snobbism that comes from playwrights and from novelists, from both sides, and in between is the lotus of the 20th-century art form: it's the screenwriter.

GIFFORD I think screenwriting is an element of film art, or rather a component of it. I wrote the screenplay for Perdita Durango, and Bigas Luna [who is going to direct it in the United States and has done his own revisions] just sent me a letter. He says, "I hope you realize I'm trying to make a good movie based on or inspired by your book, rather than simply translate the book onto the screen. This is necessarily so since I find some things quite difficult for me. They go well in your context, but somehow they have to become mine. Don't forget, you were born in Chicago and know the ins and outs of the underworld. I was born next to the Mediterranean, a little sea for little children, and I took first communion in the Romanic Monastery of Gedrables in Barcelona. But 'Perdita Durango' will be tough and sexy, haunting and unforgettable. Avanza coño."

ELGRABLY Approximately 80% of the movies seen in Europe are American-made, and 80% of those are made in Hollywood and are developed, directed, produced and marketed by a younger generation of studio people that has been called "the television generation." We wonder, does the work of the great directors of the past—Welles, Visconti, Hawks, Ford, Pabst, Fellini, Lubitsch, Wilder, Godard et al—have much influence on this generation?

GIFFORD The younger directors are people who have, for the most part, taken a look at what's gone before. You mention Fellini. I was in Rome the day he died. I arrived on the Day of the Dead. And Fellini of course couldn't get money to make movies the last ten years of his life, or longer. It was very difficult for him. The studio that he in fact made, Cinecittà, is pretty much reduced to nothing. Fellini was certainly not favored by producers and the money people, yet when he died the national television station ran his movies for the next three days, continuously, and at the bottom of the screen it said, "Il maestro."

STONE I believe the answer to that question is yes. Film schools are booming. I know that those directors' work is being looked at. I also know that attention spans are tighter and more television-oriented, smaller-screen oriented, so there's probably a marriage between the old tradition and the new, which you see on MTV. My work represents that to some degree—I'm very aware of traditional filmmaking and I'm also very aware of MTV.

[In an interview in National Perspectives Quarterly, following the hoopla surrounding JFK, Stone explained that JFK was "one of the fastest movies made. It is like splinters to the brain. We had 2,500 cuts, maybe 2,200 set-ups. We were assaulting the senses in a kind of new-wave technique. We wanted to get to the [un]conscious.

"...As a filmmaker, I do believe in what might be called 'Dionysian politics.' I believe in unleashing the pure wash of emotion across the mind to let you see the inner myth, the spirit of the thing. Then, when the cold light of reason hits you as you walk out of the theatre, the sense of truth will remain lodged beyond reason in the depths of your being, or it will be killed by the superego of the critics." Stone used this same technique in the making of Natural Born Killers.]

GIFFORD ...For me, as a filmgoer, Natural Born Killers was pretty overwhelming. At the same time, I understood that you were also trying to show how the technology is really not giving you time to catch up with events. I thought what happened in the second half of the film, in the prison, was absorbing, and Tommy Lee Jones' portrayal of the warden was terrific. There was so much truth in that because it really happened in this country a few years ago, when rioting prisoners had cut off prisoners' penises and hung them on a clothesline. What you didn't show was even more horrifying than what ended up in the movie.

ELGRABLY In her book The Reenchantment of Art, Suzi Gablick argues that we live in an era in which we all have a renewed responsibility for the survival of the planet, but that "the addictive nature of consumer society separates us from an awareness of ourselves as visionary beings." Must the artist today have a "responsible" vision to communicate?<

GIFFORD The novelist? The artist? The artist's only responsibility is to his own vision. If he wants to proselytize, let him proselytize. All I think about is the story, and what happens in the story. How it makes people feel and think and see or do is another matter.

STONE Responsibility is a word I shrink from, because it implies an outer directive, although think we all do feel a sense of social responsibility. I think the artist's vision should always seek to struggle, to expand and to conflict...As a filmmaker, I have always responded as a dreamer, not as a doer. I don't build houses, I don't make the waters run, pump electricity, explore the universe. I don't doctor to people...all I really do is dream.

[Stone's production company, Ixtlan, is named after Carlos Castaneda's Journey to Ixtlan. In that book, Castaneda learns that it is the journey that matters, not actually getting to Ixtlan, which the Yaqui Indian don Juan uses as a metaphor for an unreachable locus of wisdom. Don Juan also wanted the anthropologist to learn how "to see" the world, as opposed to merely "looking" at it.]

GIFFORD Remember what Ezra Pound said, which was "make it new." He wrote a book called Make It New. And that's all that really matters here. I think that Quentin Tarantino, to talk about the flavor of the month, is a very bright guy and an interesting filmmaker, whether he makes Reservoir Dogs based on a Chinese film, or writes True Romance based on, I don't know, Wild at Heart and Badlands, or if he makes Pulp Fiction based on a dozen different things. He has a knack for turning it into something different. In that regard I applaud him. The trouble is that when you do something well and catch people's imagination, they overpraise you, and that's problematic because you know they're later going to turn around and sock you in the jaw. André Gide suggested that a writer should lose 50% of his audience with each new book, because you know that you'll pick up that 50% that you lost, and often they're readers who never really understood your work in the first place. They were there out of fashion or for one reason or another. That's true of me, it'll be true of Quentin Tarantino, it certainly is true of David Lynch and Oliver Stone

ELGRABLY What does the future look like from here?

STONE That's an internal, organic question that you have to deal with yourself, a very personal relationship you have with your faith, your love, your heart, your creativity, your penis [smiles]. We all die, we all have our moment, our energy. Some people could say it's a decomposing universe and others would say it's a recomposing universe...I suppose I sound pessimistic, but I'm not in my heart. I'm a filmmaker. I am optimistic, but I'm taking dramatic license to be optimistic. I do feel that the media can be used for good purpose in the 21st century, that a golden age could be upon us, a higher consciousness through computers and communication. In a sort of Buckminster Fuller paradigm, people would be smarter because they have to be, in order to make the earth system work...although we are subject to the whims of the marketplace.

GIFFORD ...I don't think about the marketplace while I'm writing. Vampire books may be selling well this year but I'm not going to write a vampire book just because they're selling; I write what I want and hope there are enough people interested in both the writing and what I have to say that they buy a few copies so I can keep some food on the table.

ELGRABLY Then you don't go out of your way to exploit the media for the purposes of selling your work?

GIFFORD If you're Thomas Pynchon or J.D. Salinger, you withdraw entirely and maybe you become even more famous because of your reclusiveness. In my case, because my novels receive almost no advertising in this country, I go out on book tours, I do signings and readings and I talk to students on college campuses...I think the artist is walking a fine line, however, because the work should always speak for itself. I'm going to be dead in a little while, and whoever's left to read the books or talk about them or write about them, they're going to come to their own conclusions, and that's the best way. I think that there are a lot of very skilled performers who are writers, a lot of people who really sell their work very successfully, and others that don't—which doesn't say that one is a better writer than the other. It's a tricky business.<