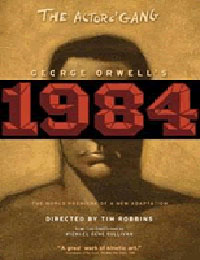

Robbins' newest play, an adaptation of Orwell's '1984,' speaks directly to the Bush administration's perpetual war on terror.

1 March, 2006 | Alternet | Jordan Elgrably

After his incandescent plays about the death penalty ("The Exonerated") and the media in Iraq ("Embedded"), it seemed inevitable that actor-writer-director Tim Robbins would continue to fearlessly produce politically charged theater.

In his newest production by Los Angeles' Actors' Gang ensemble, a corrosive play based on George Orwell's novel 1984 and adapted by Michael Gene Sullivan, director of the San Francisco Mime Troupe, Big Brother is here and torture is us.

The Actors' Gang show differs markedly from previous Orwell adaptations in that Sullivan and Robbins focus on the book within the novel, written by Big Brother's enemy No. 1, Goldstein, who argues that capitalism uses continual warfare as a means of economic exploitation and control.

"That's essential to this production," says Robbins, who directs the play. "That's where the meat is for me, because it rings so true now." Writing in 1948, Robbins points out, Orwell was not looking at the future, but "reflecting on the world around him. In fact, what he contends is that what war has really become is a way to keep the elite minority in power and to deplete the resources of the economies in the post-industrial age."

The Actors' Gang production reveals Big Brother to be an elite minority, controlling and exploiting the masses through perpetual warfare. (Wasn't it just the other day that Rumsfeld called the war on terrorism "the long war," and the Bush administration asked Congress to appropriate $439 billion for next year's defense budget?)

Speaking of government control, Robbins marvels at how Orwell the novelist did not allow Big Brother's omnipotence to concern itself with the downtrodden majority. "Brilliant how prescient he was. When you reread the book, there's a passage where they don't care about 85 percent of the people who are proles— they're so stupefied by poverty and overwork, and pacified by entertainment and by lotteries, that they're never going to be a problem. What Big Brother has to monitor and be concerned with is the other 15 percent of people who are in the upper rungs of society."

During a recent performance of the play, which opened Feb. 11 and runs through April 8, the audience appeared both entertained and disturbed by the parallels with current events: a national security apparatus eavesdropping on American citizens; the military's use of torture in prisons in Afghanistan, Iraq and Guantanamo; and "rendition"—the Bush administration's euphemism for kidnapping suspected terrorists and sending them off to regimes in Syria, Egypt or Saudi Arabia for months, even years, of interrogation.

Director Tim Robbins

Robbins' production is stark and something of a departure, the director feels, from the company's usually buoyant, satirical performances.

"This is not so much satire," he points out, "as it is a drama, and we think we found the humor in it." Humor in a hapless Winston Smith, who is tortured for nearly two hours onstage? No one said it wouldn't be twisted: ear-splitting music and electrodes are part of the interrogation arsenal; the play's humor, such as it is, comes unexpectedly and is short-lived.

Telescreens, naturally, are everywhere.

Much about this theatrical "1984" feels ominously real—nothing like the 1984 Michael Radford film that depicted a totalitarian futuristic society. Robbins is planning his own film version, to be shot in New York, "essentially the way it looks now. No big special effects, no futuristic imaginings; just the way it is."

"It's more about the mind and self-censorship," he continues. "Orwell writes about acquired self-censorship, the idea that Big Brother is present if you allow him to be present. There are many people living in fear, and that's really what he was writing about—totalitarianism of the mind."

Robbins balks when asked about critics who accuse him of agitprop. "It seems that anytime someone questions something from the left, or from a progressive point of view, there is an immediate rush to label it 'political,' as a way I think to marginalize it as a work of art. I find that offensive."

Robbins has stuck his neck out repeatedly over the years, with repercussions for both himself and his family—he has two children with actor and activist Susan Sarandon; when the couple spoke out against the Iraq war, they received death threats and had major public appearances cancelled.

Robbins accuses the entertainment industry of being far more conservative than we are led to believe. "I'll bring up the most crucial time in the last ten years, right before the Iraq war; Hollywood was essentially silent about that. I had many people tell me 'Now's not the time to protest.' Well, if now's not the fucking time, when is the time?"

But exercising his First Amendment rights, Robbins insists, has not hurt his career. "It doesn't hurt you to use your freedom," he says, "and if it does, then why have freedom? They told me before the first Iraq war, 'Don't go down to Washington and protest; it's going to hurt your career.' And the next two years brought Bob Roberts and The Player, and afterwards Shawshank Redemption and Hudsucker Proxy; after this war I won an Oscar for Mystic River.

Doublethink and Newspeak are still prominent features of Robbins' "1984," and never has this nightmare had more resonance than today, when the neo-conservative agenda of the Bush administration has capitalized on fear-mongering and division as a form of mass control. Robbins argues that throughout the Reagan-Bush years, through Clinton and until today, right-wing talk radio and other media have waged an effective campaign against the left and the Democratic party, while fostering hatred of Americans by Americans.

"Well, now they've got it all," he says. "They've got the executive, they've got the Congress, they've got the judicial for the most part, and things are worse. And sooner or later, if Joe Sixpack doesn't figure this out, that he's been lied to for the past 25 years."

"I'm not the enemy," Robbins says. "I've been advocating for the American worker, for peace and justice. That's not the enemy. The enemy is people who make you believe that hatred is necessary in this country, because all your hatred is doing is buoying up and keeping in power people who do not have your best interests at heart, people who will not represent you in Washington. They will close down your factories and sell off the jobs to the highest bidder in China. How un-American is that? But somehow these people are aligned with God and country, and this illusion has been sold for the past 25 years. It's very clever, very effective propaganda."

If today's citizenry lack a sufficient culture of dissent, Robbins says, it may be the result of too much comfort. "People believe they're comfortable. We're locked into our telescreens and we believe; we buy into the culture of entertainment and distraction and advertisement."

Few celebrities in Robbins' position of power are making themselves heard beyond the pale of mass entertainment. With the recent exception of George Clooney, the list of progressive entertainers willing to speak out publicly is still painfully short.

Could the Bush administration be spying on outspoken Americans with a liberal agenda?

Says Robbins, "Certainly I think the reason they are being so secretive about [wire-tapping] is they've fallen into that Nixonian trap. They're so paranoid about their own lies and deceptions that they feel like they have to monitor their opposition."

If "1984" is 2006, and torture is what Americans do to extract information from the enemy, Robbins still refuses to play his cards close to the vest, to avoid Big Brother's scrutiny. The government may be watching him, he says, but "paranoia is a sign that you're losing the battle."